|

In America today heroes have been replaced by bureaucrats. When

we mention historical figures, if we mention them at all, it's gossip:

Kennedy's affairs - real or alleged; Franklin D. Roosevelt's likewise;

Jefferson's children by Sally Hemmings. The truth remains that America

has produced heroes, famous and not-so-famous men and women from

eras when public achievements were venerated and personal matters

left alone.

Fremont Older (1856-1935) was one of our heroes. Born into an impoverished

Wisconsin family whose men had been wiped out in the Civil War,

Older had a Dickensian boyhood, and it could not have been coincidence

that his favorite author was Charles Dickens. Coming to San Francisco

in 1873, he drifted from one printer's job to another in pursuit

of his boyhood dream of becoming an editor, until a chance encounter

got him a job in Redwood City, California, launching his journalistic

career. His unusually sympathetic and probing reportorial style

got him noticed back in San Francisco, and after returning to the

city as a reporter he moved rapidly into editorial positions.

In 1895 Older got the chance of a lifetime when the owner of the

moribund old San Francisco Bulletin offered him the position

of Managing Editor. Older wrought a transformation in the paper

that is practically unparalleled in any business: in less than a

year the paper had new quarters, new equipment, new staff, and boasted

the largest circulation of any afternoon newspaper west of Chicago.

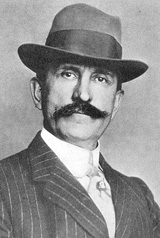

Fremont Older c. 1910.

Older had a unique gift for attracting and developing

talent, and Bulletin staff included such names as Robert

Ripley (Ripley's Believe It or Not), Rube Goldberg, Robert

L. Duffus, Maxwell Anderson (Key Largo, Anne of the Thousand

Days), and Rose Wilder Lane, who co-authored the Little House

series with her mother Laura Ingalls Wilder.

Older's journalism was populist, and to be sure, sensational, but

below the sensationalism lay a bedrock of uncompromising rectitude.

Older's rectitude almost cost him his life on at least three occasions.

After San Francisco voters handed Older and his reform allies a

bitter defeat in 1905 by re-electing the corrupt administration

of Mayor Eugene Schmitz, a tool of boss Abraham Ruef, Older initiated

the Graft Prosecution that got Schmitz and Ruef convicted of extortion.

The prosecution did not just go after a few corrupt politicians.

Wealthy and prominent San Franciscans faced indictment and possible

conviction for conniving with Ruef-Schmitz, and they fought the

prosecution with every imaginable weapon: detectives, and hoodlums

harassed prosecution members; the Oakland home of one of Ruef's

former supervisors was dynamited; Older and his wife Cora were themselves

the target of a dynamite plot; and Older was kidnapped on Van Ness

Avenue in broad daylight under cover of an arrest warrant issued

in Los Angeles, rushed at gunpoint out of San Francisco by car,

and put aboard a southbound train; he survived only because a young

lawyer whose identity was never revealed heard the kidnappers say

something about giving Older "a run through the mountains."

The lawyer got off the train at Salinas, telephoned San Francisco,

and Older was rescued in Santa Barbara.

The graft prosecution ended when the defendants managed to elect

their own District Attorney, the corrupt, incompetent Charles M.

Fickert. Ruef alone of all the defendants went to jail, and then

Older did something that astounded everyone: reasoning that it was

wrong to pick out a single individual for punishment when it was

the system that had to be changed, he went to San Quentin, held

out his hand to Ruef in the visiting room, said he was sorry for

much he had done, and asked forgiveness. The Bulletin campaigned

for Ruef's parole after a year. Famous and ordinary men and women

trooped to Older's office with stories of their lives, pleas for

help, or just to talk. He was called "Father Confessor to a

City."

Fremont and Cora Older built a house of a uniquely livable California

design above Cupertino, California, but they were not destined for

a quiet retirement. Labor and management continued to clash in San

Francisco, and in 1916 there was a bitter waterfront strike. Thomas

J. Mooney, a self-proclaimed organizer who went from one cause to

another and had been tried and acquitted of conspiring to dynamite

utility towers, and Warren K. Billings, a transient from New York

State who had been convicted of transporting explosives in a set-up,

attracted the attention of the "Law and Order Committee"

of San Francisco's Chamber of Commerce. In the United States there

was bitter ethnic and political division over the Great War in Europe,

General Pershing's incursion into Mexico, and the Easter Rebellion

in Ireland. San Francisco was the world in microcosm: Bulletin

reporter Ernest Hopkins said the city was "neurotic with civic

and labor strife."

The volatile mix exploded on July 22, 1916 during a great patriotic

"Preparedness Day" parade when a bomb killed ten people

and wounded forty others. Older was a confirmed pacifist, but he

predicted that he would get blamed for the bomb. He and other pacifists

were. Billings and Mooney were arrested and tried. Billings had

a convincing alibi, but he was convicted of murder and sentenced

to life imprisonment. Mooney was tried shortly afterwards. His defense

produced an even better alibi, but a surprise prosecution witness

testified that Billings, Mooney, Rena (Mrs. Tom) Mooney and another

defendant drove down Market Street in a jitney during the parade

and deposited the bomb.

Older believe Mooney guilty until the defense unexpectedly discovered

letters of the chief prosecution witness that suggested he was not

in San Francisco when the bomb went off and that the prosecution's

case was fabricated. Older was in a terrible position: his publisher

was a conservative old gentleman who didn't want any more fights,

but Older was absolutely dedicated to the mission of the fourth

estate. The Bulletin printed the letters. Older and the defense

discovered perjuries by other prosecution witnesses and The Bulletin

kept up the fight, but in 1918 Older got an ultimatum to drop the

case or be fired. In this horrible situation he was rescued by William

Randolph Hearst, who had been trying to hire him for years.

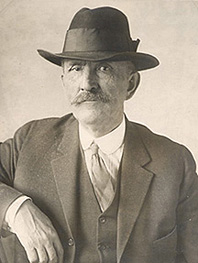

Fremont Older, 1919

Now editor of Hearst's evening Call, Older

printed the report of a Federal investigator who had planted microphones

in the District Attorney's office and recorded the prosecution,

among other things, plotting to convict Rena Mooney by blackmailing

witnesses. Tom Mooney's execution was only three weeks away, and

President Woodrow Wilson intervened with the Governor, who commuted

Mooney's sentence to life imprisonment. There followed a long, drawn-out

fight to free Billings and Mooney. The injustice of their case and

the senseless destruction of World War I made Older a confirmed

pessimist about the human race, but he never stopped trying to help

people. Billings and Mooney were freed in 1939 after twenty-three

years in jail, but Older did not see it. On March 3, 1935, he had

collapsed at the wheel of his car and died of a heart attack while

driving Cora and their ward Mary back from a camellia show in Sacramento.

His last words, when they came back to the car in which he had been

writing a column on the essayist Michel de Montaigne, were "If

you had waited fifteen more minutes, I would have finished."

|